This essay on New Labour, digital media, and network ideologies appeared in The Globalization of Corporate Media Hegemony, edited by Lee Artz and Yahya R. Kamalipour (State University of New York Press, 2003)

Over the last five years, so much has been written about the internet and the so-called knowledge economy that it may appear as if nothing new could be said about the matter. We have heard countless times the techno-utopian argument that the internet will change society, the economy and politics, making the world a more efficient, peaceful and democratic place. When these techno-utopians joined with venture capitalists in the mid-1990s, they helped to create the huge enthusiasm for a ‘new economy’ based around the idea that trade in information would replace trade in physical goods.

Over the last five years, so much has been written about the internet and the so-called knowledge economy that it may appear as if nothing new could be said about the matter. We have heard countless times the techno-utopian argument that the internet will change society, the economy and politics, making the world a more efficient, peaceful and democratic place. When these techno-utopians joined with venture capitalists in the mid-1990s, they helped to create the huge enthusiasm for a ‘new economy’ based around the idea that trade in information would replace trade in physical goods.

Barely discernible at first, then gradually getting louder, were the voices of the techno-pessimists. They counter-argued that current technological changes would only bring insecurity, joblessness and moral deterioration. With the collapse of new economy share prices in March 2000, the techno-pessimists have had a wider hearing. Their view is a mirror image of the utopian view. For each of the utopian claims that technology will cause a positive change, they counter with negative changes. Yet ironically they share a lot of assumptions with the utopian position. They share the view that technology is going to bring about large upheavals and that these are inevitable; further, they both share the assumption that changes in society and economy can be predicted from the process of technological innovation itself.

The settled view now emerging from the more sophisticated commentators borrows elements of both the utopians and the pessimists, and emphasises a longer-term and more complex view of technological change. On this view, today’s internet and new economy do indeed mark the beginning of a prolonged era of change. We can only know at this stage the rough outlines of how technology, economy and society will co-exist, even in the very near future. All we do know is that we need to combine attitudes of flexibility and control, to be prepared to adapt to rapid change as well as to regulate and manage it. There will be a mixture of negative and positive changes, but what is certain is the fact of change itself – that much is inevitable.

This view improves on the simple technological determinism of the techno-utopians and pessimists. However, in its own way, it remains a dangerous view, which serves the interests of particular social blocs, to the detriment of others. It is a view that confidently elides social contradictions and suggests that easy leaps can be made from open technologies to open markets to open societies to open minds. But it is precisely at the join between technology and society where all the most important questions about the internet remain to be asked, and where so many commentators remain silent.

In spite of this, the view that we are embarking on a period of inevitable rapid change towards a new economy or knowledge society has become increasingly influential. In Britain, Tony Blair has placed the transition to a knowledge economy at the centre of his governments’ strategy and has sought to define a political Third Way, based on the imperatives of a new globalised knowledge economy. Within Blair’s own Policy Units, a cadre of new economy intellectuals has been recruited to define this agenda and map out how new forms of government and public service might coexist with the knowledge economy. This new economy agenda now dominates the ruling elites of Britain to such an extent that it is difficult to imagine its weakening through a change of government. Yet the road to hegemony for the new economy idea has been remarkably smooth. The only obstacles that have been put in its way are those of falling share prices, rather than substantial intellectual critique. And plummeting share prices since March 2000 have done little to dent its confidence.

In the following pages I want to examine how in Britain the internet as an idea, a way of doing business and of organising society, has grown in influence and come to provide one of the main ideological supports for the 1997–2001 government. I want to consider how the metaphor of a network has emerged as a new paradigm for imagining how to organise society more inclusively and openly, with less hierarchy and conflict. Yet this paradigm leads to support for the self-regulating market and neoliberal globalisation, the very processes which worsen exclusion, division and stratification. I want to describe the new cult of the entrepreneur, the folk hero of the new economy and how a contradiction is developing between the British state’s interest in preserving the racist anti-immigration laws introduced from the early 1970s and the view that migration of skilled IT-walas from Asia may be needed to support innovation in the new economy. I want to ask why the transition to the new economy brings with it greater corporatisation of public services, along with competition and market values, in areas previously immune to their power.

I am therefore less interested in the internet’s number of users, their social backgrounds, the number of web pages hit or the number of e-mails sent, than I am in how the internet is being discussed and described by policy-makers. I am less interested in how many government services are available online than in how the ruling elites are talking about the need for public sector services to be reinvented as something called ‘e-government’. I am less interested in the rise and fall of new economy share prices than I am in the weakening of the weakest sections of society.

The seduction of silicon

During the mid-1990s, Britain had become a place in desperate need of change. Thatcher’s energetic revolution-from-above, her attacks on the post-war Keynesian consensus, ‘gentlemanly rule’ and the old cultural elites, and their substitution with the values of middle-class entrepreneurialism and market forces, had waned. All that was left was John Major’s reassurances to an ageing Home Counties audience that England would be forever village cricket, warm beer and old maids cycling to church through the morning mist. Many now looked to Tony Blair as harbinger of a much needed ‘modernisation’.

Blair had taken charge of the Labour Party in 1994 at a time when it had not won a general election since 1977. Emulating Clinton’s success in winning back the political ‘middle ground’, Blair was able to make the party acceptable to middle-class voters by dropping the historic commitment to nationalisation, becoming ‘business-friendly’ and by abandoning policies aimed at redistribution of income. This was combined with a new ‘tough’ stand on law and order issues which had, until then, been perceived as Labour’s achilles heel. Denied political power for so long, most Labour Party supporters believed that Blair’s shift to the political Right could be justified if it won them office. In the 1997 general election the strategy paid off, as large numbers of middle-class voters in marginal seats switched to Labour, giving them a majority in Parliament even larger than the Attlee government of 1945. Meanwhile an increasing number of business managers, journalists and intellectuals had been returning from visits to California with tales of a new economy based on the internet, new ways of doing business and vast potential profits. In the pages of the San Francisco-based information capitalist magazine Wired, the new economy was celebrated with a Panglossian optimism, out of kilter with the grey mood of the time. The contrast between an old, clunky and unimaginative Britain and California’s apparent light-footedness was striking. With the Cold War over, and globalisation of the world economy marching ahead, the future of the world seemed to be in Silicon Valley and Britain needed to get a piece of the action.

It was inevitable that Tony Blair’s Labour Party would be attracted to the Silicon Valley model, with their shared emphasis on constant modernisation, and penchant for all things new. The love affair was sealed through a number of go-betweens. The intellectuals gathered around the Demos ‘think-tank’ 1 – which played a key role in defining the Blairite agenda – began to articulate the Silicon Valley model into a set of policy ideas for Britain. Charles Leadbeater – who believed that Britain should emulate Silicon Valley’s ‘network-based industrial system which promotes rapid collective learning and flexible adjustment’ (Leadbeater 2000, p141) – joined Geoff Mulgan, co-founder of Demos, as advocates for this agenda at the highest levels of government. Mulgan was recruited as a key adviser in the Downing Street Policy Unit, once Blair was in government from 1997. Peter Mandelson, widely credited as the chief strategist of New Labour’s rise, took a particular interest in the knowledge economy and, while heading the Department of Trade and Industry, was an admirer of the Californian model.

By 1999, interest in all things internet-related reached new heights in Britain. The excitement of e-commerce infected a popular audience as a result of the massive rise in access to the web, magazine articles on ‘e-millionaires’ and television adverts which portrayed a shiny new world of electronic opportunity. And the glamour of the new economy rubbed off on the government, which had placed the internet at the heart of its agenda.

The ideology of the network

The techno-pessimists are wrong. It is not the internet itself that is dangerous, but the idea of the internet as a symbol of free trade.

The internet is an electronic communications medium. It resembles the telegraph and telephone systems insofar as it is arranged as a network, with each point on the network capable of both sending and receiving communications. It differs from these insofar as the quality of communication is far richer, offering visual as well as textual and aural elements. In the subsection of the internet known as the web, it also allows a form of broadcast communication, analogous to television or radio, although the arrangement of the web into generally static ‘pages’ of illustrated text suggests a resemblance to print media.

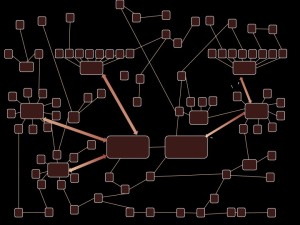

But for many of our current intellectuals, the internet is far more than a new communications medium. They have been seduced by the idea that the internet – or, more precisely, its networked structure – is a metaphor for a new capitalism. For these writers, the network represents progress out of the old world of machine-like bureaucracy, hierarchy and control, in favour of creativity, innovation and freedom. Like earlier mythologies of capitalism, the network model explains away capital’s contradictions and naturalises its social relations, often using biological imagery. The inconvenient reality of systematic unequal distribution of resources among different social or national groups is glossed over.

Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the corporate-sponsored Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a major investor in Wired magazine, pioneered the networkist model of capitalism through the 1990s. He argues that the emergence of this new order is inevitable and organic, ‘like a force of nature’ (Negroponte 1995, p229). ‘The agent of change will be the Internet, both literally and as a model or metaphor. The Internet is interesting not only as a massive and pervasive global network but also as an example of something that has evolved with no apparent designer in charge.’ (Negroponte 1995, p181)

Many on the centre-Left have been attracted to this vision, from Manuel Castells’ (1996) three-volume analysis of what he calls the ‘network society’, to high-profile commentator Jonathan Freedland, who celebrates the end of an old world of division in favour of one defined by integration and symbolised by the web: ‘It is a hopeful symbol: a collection of loose, frail threads tying one individual to another’ (Freedland 2000, p16). In Britain, the two leading Left intellectuals of the network vision are Charles Leadbeater and Geoff Mulgan, who have each crafted a version of the network ideology which has become a central theme of the Blairite script.

According to the theorists, as knowledge becomes the dominant factor in production and delivery of services, organisations will increasingly form themselves as networks. In a networked organisation the emphasis is on horizontal linkages between units in a co-operative organisational structure, rather than on vertical linkages from the top downwards. The horizontal network favours initiative, responsibility and self-organisation, rather than the unthinking implementation of a superior’s ideas. Knowledge is encouraged to spread across different units in the network, rather than being solely in the hands of the executive layer of a hierarchy. The network form of organisation is seen as more agile and able to adjust to change. Its decentred nature allows it to evolve organically.

‘[A]s a rule the availability of more bandwidth, more communicational tools and more opportunities for horizontal communication tends to favour what I have called weak power structures, structures based on the economical, light sharing of information rather than the hierarchical strong power of mechanical systems where most of the organisation’s energy is used to maintain internal control.’ (Mulgan 1998, p154)

Power is seen as withering away as the network becomes self-organising and dispenses with a tight command structure. Moreover networks are thought to be more inclusive, encouraging diversity and individuality. With each unit allowed some autonomy, confidence and mutual trust grow in a ‘virtuous circle’ (that is, a positive feedback loop), as different units develop their own identities. The concept of ‘social capital’, currently fashionable as a leitmotif of Third Way writing, is used to describe this reservoir of mutual trust. ‘Networks are not held together by hierarchy or structure but by relationships and social capital.’ (Leadbeater 2000, p126)

Firms, economies, media, the relations between nation-states – all are becoming organised more like networks, according to Leadbeater and Mulgan, with all the associated advantages of democratisation, empowerment and inclusivity. The network concept is used as a master key to open up all conceptual barriers, in the same way that the word ‘text’ was used by postmodernism. For the networkists, there is nothing outside of the network. Society itself is described as an information network. Technology and society are collapsed together so that the issue of how technology interacts with society cannot be asked: ‘technology is society’ (Castells 1996, p5).

Indeed, for these advocates of ‘globalisation with a human face’, the tightening integration of the world economy is itself best understood as a series of networks across the world, rather than as a set of power relations. The networkists describe a world freed from structural divisions, a frictionless world where knowledge, confidence and wealth flow easily over dwindling national boundaries. The mass of communication networks across the world constitute an information biosphere – a single, interconnected information organism of free expression and free trade. The growth of free market globalisation is presented as an inevitable result of technological progress, rather than a normative choice on the part of the ruling elites. As proven by the recent French ban on internet sales of Nazi memorabilia, the inevitability is a concoction. 2

The internet, as we have seen, is celebrated as a technology without a design, able to develop autonomously and intelligently, free of centralised control. When the internet is taken as a metaphor for society, the same idea of an order without central points of command is powerfully suggested. Society is conceived as a set of interconnections dispersed so thinly that it no longer makes sense to speak of centres and peripheries of power – an account similar to that given in the post-structuralist thought of Michel Foucault. 3

‘Much of the baggage of sovereignty and power that we have inherited from the days when the main role of government was to protect us from danger is now obsolete, and states are now making the uneasy transition from thinking of themselves as pyramids, with clear boundaries and clear lines of command, to something more like a flotilla where no one is in absolute command.’ (Mulgan 1998, p197)

For a world in the throes of free trade globalisation, where multinational corporations occupy more and more areas of life, the postmodern image of society as a decentralised network in which there are no centres of power, is a useful enough ideology. As the subtitle to Leadbeater’s (2000) book suggests, questions of power and society are obsolete – they have evaporated into ‘thin air’. With everything on the move, power becomes meaningless and movement is everything. Yet for all the apparent change, innovation and movement, the grip of race, class and corporate capital is stronger than ever.

Open markets, open society, open minds?

The network ideology blends these postmodern themes with respect for market forces. The orthodox neoliberal interpretation of the market – where the threat of closure drives down costs – is swapped for a benign view, adapted for the knowledge economy, in which the free market is the natural font of innovation.

Information networks are imagined as free markets in ideas. If ideas are commodities, natural selection will automatically finance the most popular. Indeed, networkists see the internet as potentially the ultimate market of ideas, with free expression overlaid on free trade in a process of near-perfect competition. Bill Gates is just one among many to argue that the internet will increase market efficiencies, a view he last espoused when invited to speak at the World Economic Forum in Melbourne, September 2000. 4 The globalisation of e-commerce – which implies both the expansion of network infrastructure and the imposition of a legal framework protecting corporate rule across the globe – is seen as, not only contributing to economic growth, but also as inherently democratising.

Repeating the old capitalist mythology of the nineteenth century, the networkists present the market as a free arena, open to anyone. Today in the knowledge economy, the trade in goods, land, labour and money has been eclipsed by the trade in ideas. The free market in ideas is seen as an essential environment for the fostering of innovation. The usual threat to market efficiency – monopoly – is thought to be less of a concern in the new economy, since knowledge capital is regarded as having a limited lifespan of usefulness and so is less likely to lead to protection. What is usually ignored by the networkists is the fact that there are good reasons to think that the knowledge economy is more likely than others to suffer from monopoly distortions, as a result of economies of scale (Kundnani 1998). Furthermore, the much vaunted openness of the new economy belies the fact that multinational corporations – AOL-Time Warner, IBM, Microsoft – dominate the sector. In telecommunications, the top ten firms now control 86 per cent of the world market (Harris 2001). In computer software and manufacture, the dominance of a handful of players is even greater.

Networkists are in awe of the corporate world which seems to them to be the only place where new ideas are thriving. The belief that creativity is the sole preserve of corporations leads to a new legitimisation of corporate power, even where, as in the Microsoft case, that rule is monopolistic. Attached to this toadying to private firms is a clear message that, in an age of innovation, the state has failed to keep up. Few can now remember that the internet itself was invented in state-funded universities.

The cult of the entrepreneur

At times, the network philosophy appears to be nothing more than the fancies of the digerati, the world made over in the image of the corporate nerd who thinks about all relationships in terms of technical problems. But since the net became a target of commercial exploitation from 1995, the nerd has been replaced by the entrepreneur as the public face of networkism. The entrepreneurs have become the folk heroes of Blair’s Third Way. They neither own machinery nor sell their labour power – they have nothing to sell but their ideas. According to the cult of the net entrepreneur, they are buccaneers in the fast-moving world of the new economy, never staying in one place for very long. Drivers of creativity and innovation, the power that accrues to any one of them is ephemeral since they are only as good as their last idea. Yet many are fabulously wealthy. 5

The old yuppie image of the entrepreneur from the 1980s has given way to one of Bohemian flair and intelligence. The new entrepreneurs are casually dressed, apparently everyday folk. They appear to create wealth, not through mass production, with all its connotations of monotonous labour, alienation and exploitation, but in the knowledge economy, where workers use their brains not their hands.

The glamour of entrepreneurialism can make the sleaziest multinational smell of roses. For years, Microsoft was able to present itself as the plucky entrepreneur fighting the corporate imperialism of IBM. By the time the conjuring trick was exposed, Microsoft’s accumulated power reached as far as the Philippine police force, who had been ordered to conduct raids in schools for pirated copies of educational software (Kundnani 1998). Yet Bill Gates was welcomed to Britain in Tony Blair’s first months of government and recruited as a ‘special adviser’ for Britain’s use of technology in schools.

It is the cult of the entrepreneur that has enabled New Labour to justify a deepening process of corporatisation. Indeed, a major concern of Third Way politics is the attempt to spread the values of net entrepreneurialism to the public sector, in order to ‘save’ it. ‘Government must behave like an entrepreneur’ and create ‘a vital synergy between business and government’ (Mandelson 1999).

Clean capitalism?

For the Third Way intellectuals, the transition to a knowledge economy promises the Holy Grail of social democracy, a reason for thinking that capital and labour are no longer opposing forces, a clean capitalism where conflicting interests can all be absorbed into a mutually beneficial social contract of knowledge creation. But the knowledge economy does not dispense with the dirty side of capitalism; it merely displaces it to the poorer parts of the world, where it becomes invisible. 6 The networking dream does not help the Third World sleep any easier. It is no coincidence that Nike is both Leadbeater’s (2000) archetypal networking firm, and a major exploiter of cheap labour. Its strategy of concentrating purely on the design of its shoes and their marketing, while their physical assembly is ‘outsourced’ to the Third World, is seen as innovation in the knowledge economy. The First World concentrates on producing the knowledge, the Third World on making the economies.

One person’s network is another person’s hierarchy. But the new economy ideologues choose not to see what is outside their own networked universe. From their perspective, it becomes possible to imagine a politics without adversaries, yet another resurrection of the 1950s ‘end of ideology’ thesis: ‘Politics can look less like a competition between blocs to get hold of a static pool of power, and more like an information system attempting with varying degrees of success to aggregate millions of preferences, to devise common solutions and to mobilise changes in public behaviour such as harder work, better parenting, or greater willingness to obey laws.’ (Mulgan 1998, p155)

Capitalism supposedly now has a vested interest in inclusivity because a knowledge economy requires everyone’s talent to be valued. The reserve army of labour is a thing of the past. Labour-power itself has been replaced by ‘human capital’. ‘An innovative economy must be socially inclusive to realise its full potential. If we write off 30 per cent of the population, we are writing off a lot of knowledge, intelligence and creativity.’ (Mandelson 1999). To maximise the circulation of knowledge – Blair’s mantra of ‘education, education, education’ – is to create economic opportunity as well as political empowerment. This is a unique opportunity for the centre-Left, according to Leadbeater, Mulgan, Mandelson and Blair.

But it is also an opportunity for business. In line with the overriding promotion of market values, entrepreneurialism and network technology as panaceas for all social ills, the corporations are invited in. The contradiction between the desire for high quality comprehensive education, and the unwillingness of the rich to fund it, is resolved through commercial sponsorship. The cost of investing in computers for schools can be paid for by supermarket chains who are rewarded with added value to their brand names. The National Grid for Learning – Blair’s ‘ambitious’ scheme to link all schools to the internet – can be paid for by British Telecom, who instantly get privileged commercial access to the educational software market. In Education Action Zones – local mechanisms for bringing private money into schooling – children are supplied with ‘resource packs’ produced by McDonalds. Music teachers are advised to encourage pupils to make up words for ‘Old McDonald had a store’, to the tune of ‘Old McDonald had a farm’ (Cohen 1999, p179). Britain is moving towards the American model where schooling is a commodity, widely traded on the stock market, and worth $650 billion (Monbiot 2000, p331).

E-government

Along with the corporations comes a banal optimism, in which social problems – such as a class-ridden education system – become a matter of technical problem solving, a failure to innovate, rather than a lack of political will or democratic accountability. What is needed is a new breed of social entrepreneur, to apply a corporate approach to innovation in the public and voluntary sectors. ‘We need to embark on a period of sustained and intense innovation in our civic institutions, to create a new civic culture to accompany the dynamism of the new economy’ (Leadbeater 2000, p168). Inevitably competition is seen as the basis of progress. Leadbeater suggests that the National Health Service will, in the future, compete on the internet in a global healthcare economy (Leadbeater 2000, p247).

The envisaged transformation of the public sector will, of course, require corporate ‘expertise’. More than half the places on New Labour policy task forces have been given to big business (Cohen 1999, p179). The management consultants have been lining up to profit from the creation of ‘e-government’. Deloitte Consulting, anticipating the growing need for governments to be told how to do things by corporations, has established a ‘Public Sector Institute’. In a report entitled ‘At the dawn of e-government’, the consultants advise that: ‘transformation is what e-Government is all about, and with Internet applications powering streamlined service delivery and supported by the best staff and IT infrastructure, governments will evolve into new enterprises that bear no resemblance to their structure today’ (Deloitte Consulting 2000, p4).

But the vast amounts of government money poured into IT projects to date – where the state has contracted firms such as Siemens, EDS and ICL – have usually ended in disaster. There have been over thirty failed schemes since Labour came to office, resulting in billion pound losses. Of course the public purse is expected to underwrite this ‘risk’ – such is the price to be paid for introducing the spirit of entrepreneurialism to government.

Britain rebranded

Techno-utopianism is often met with scorn on this side of the Atlantic ruling class; the British elites have traditionally associated the right to rule with study of the arts, rather than science and engineering. But in a country that prides itself on being the home of the industrial revolution, technology is never far away from the perennial calls for ‘modernisation’. Like Harold Wilson before him, Blair has flung himself at new technology with boyish enthusiasm, hoping to make it the linchpin of a new national self-image, in which Britain can once again bestride the world, this time as ‘the world centre for e-commerce’. No longer happy to play Greece to America’s Rome, New Labour believes that in the knowledge economy, Britain can retake its rightful place as a major economic power, taking advantage of a ‘tradition for inventiveness’ and the spread of the English language, rather than relying on the old faiths of Empire, military strength and sterling.

In December 1998, Peter Mandelson launched the white paper ‘Our competitive future: building the knowledge-driven economy’ and made it clear that the internet was now regarded as a vital tool for economic development. At the launch, Mandelson said that ‘Britain must become a leading nation on the internet, which is now the fastest-growing market place in the global economy’ (Thompson 2001). The following year, Blair set out his aim of making the UK ‘the best environment in the world for e-commerce’ (Performance and Innovation Unit 1999, p1). In a flurry of new initiatives, action plans and reports, the government has tried to define an agenda for techno-Britain. An ‘e-envoy’ has been followed by an ‘e-minister’ to oversee the development of internet trading and to put government services online. The great hope is that London can keep a leading role on the world economic stage, through knowledge capital instead of finance capital. But whether the plan succeeds may depend on Blair tackling the deeper problems in British society – a class system that hinders creativity, and leads to massive variations in the regional distribution of wealth; immigration laws which exacerbate labour shortages and legitimise institutional racism across society; a legal system that gives no protection from corporate excess; and the absence of a culture of accountability in the public services.

The solutions to these problems will not come about by applying corporate models of ‘customer-centric government’ like those recommended by Deloitte Consulting (2000, p1): ‘Historically citizens’ perception of government service has been less than glowing. When they think about the prospect of contacting the government in almost any way, they picture long waits and cumbersome procedures… Today, leading governments are changing both perception and the reality by giving top priority to the customer.’ As Tom Nairn (2000, p77) points out, the shift from British ‘subject’ to ‘customer’ should not be confused with true political citizenship. ‘Unable to implement a new conception of the state, Blairism had defaulted to the model of a business company… This is neither ancient subjecthood nor modern constitutional citizenship. It is more like a weak identity-hybrid, at a curious tangent to both.’ The conservatism of the British state – its claim to represent an unchanging cultural essence handed down through the generations – survives this ‘modernisation’ and, when necessary, can be wheeled out again as the basis for a regressive nationalist allegience (Kundnani 2000).

The American dream

The model, as ever, in Britain’s attempts to reinvent itself, is the American variant of capitalism. In the hands of Leadbeater and Mulgan, the network philosophy is an attempt to import what are perceived as the best aspects of that country’s system – a more ‘flexible’ labour market, greater social mobility, technology-driven economic growth, more corporate ‘freedoms’ and a more liberal immigration system. It is assumed that these can be separated from the worst aspects of the US model – the huge entrenched economic inequalities and the brutal state racism by which inequality is protected and legitimised.

A major line of fissure in this project is on the question of immigration policy, where the needs of the new economy – for overseas skilled labour – clash with the racism that led to the end of ‘primary’ immigration following the 1971 Immigration Act. The networkists argue that migrants are likely to be enterprising and creative, a potential pool of talent not to be wasted. Their contribution to the development of Silicon Valley is highlighted. The Valley itself is reckoned to support a ‘cosmopolitan openness’ so that ‘many of its biggest companies are run by post-war immigrants’ (Leadbeater 2000, p141). Jonathan Freedland, witnessing the naturalisation ceremony performed by recent arrivals in the USA, comments: ‘It was an extraordinary sight. Immigrants, elsewhere tolerated and often loathed, were being embraced by an official of the United States government. Dark-skinned foreigners were not being cast out, but ushered in’ (Freedland 1998, p141). The implication is that Britain could reap the advantages of following an American-style immigration policy, if only the inertia of Britain’s imperial past – and its racism – could be overcome. Furthermore, for Leadbeater and Mulgan, the new economy renders the rules of physical territoriality less significant than the networks of information flows. ‘Today the [territorial] boundaries are still there but instead you see economies, and the centres of power are not walled, but rather the hubs of creativity and exchange’ (Mulgan 1998, p69).

But wall-building is on the rise. The USA-Mexico border – a crossing that activists believe claimed the lives of at least 1,600 migrants between 1993 and 1997 – is increasingly fortified with barbed wire fences, security patrols and surveillance technologies (Campaign Against Racism & Fascism, 1999). Meanwhile corporations, such as Wackenhut, profit from the industrial warehousing of immigration detainees – an estimated $500 million business, now expanded to the UK (Campaign Against Racism & Fascism, 2000). It is not that US immigration policy is more ‘liberal’. Rather, with the gradual evolution of a system of national origin quotas, encouragement of overseas recruitment by US corporations and minimal welfare provision for new arrivals, it is more finely tuned to the developmental needs of industry. The American IT industry, for example, is able to use Indian computer programmers whose education has been paid for by a poorer country. The Indian Institutes of Technology – Nehru’s hopeful springboards for an independent, scientific and prosperous India – have become finishing schools for American capitalism.

Britain, on the other hand, has moved from a period of post-war reconstruction, during which a cheap, black immigrant workforce was recruited through colonial connections, to the principle of zero immigration from outside the European Community bloc – on the assumption that free movement within a ‘Fortress Europe’ would cater for all of Britain’s labour needs. But the ‘Fortress Europe’ system has failed to provide a sufficient supply of workers at the bottom end of the British economy. As a result, this gap has been filled by a growing under-class of Third World and eastern European immigrants – usually themselves exiles from the devastation wrought by neoliberal globalisation – entering Britain either without documents or through the asylum system. ‘[T]he refugees, migrants and asylum-seekers, the flotsam and jetsam of latter-day imperialism – are the new under-class of silicon age capitalism. It is they who perform the arduous, unskilled, dirty jobs in the ever-expanding service sector,who constitute the casual, ad hoc, temporary workers in computerised manufacture, who provide agribusiness with manual farm labour… They are, in a word, the cheap and captive labour force – rightless, rootless, peripatetic and temporary, illegal even – without which post-industrial society cannot run’ (Sivanandan 1989, pp15–16). In addition, Britain is unable to fill shortages of skilled workers in nursing, teaching and the IT sector.

The result is that immigration to Britain is unplanned and undocumented – and, therefore, provides little guarantee for capital that incoming labour meets its needs. Consequently, for the first time since the early 1980s, a racialised debate on immigration is high on the political agenda, and the conservative press is calling for ‘the drawbridge to be raised’. The alternative offered by the Blair government is a twofold ‘modernisation’. First, there is to be a review of the commitment in the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees, which obliges the state to provide due legal process to all applications for asylum, whatever their circumstances. Second, following the American model, a limited amount of direct recruitment of overseas skilled workers is to be allowed, to meet specific needs of the economy. The ‘economic migrants’, currently abused en masse, will be screened and sectioned off into categories of skilled and unskilled, wanted and unwanted. As such, Blair’s attempt to match immigration policy more closely to the needs of the economy, like his other reforms, will leave in place the substance of Britain’s conservatism.

The phony revolution

In Britain, the New Labour government has celebrated the internet as more than just a new communications technology, but as an icon of a new globalised world of free trade, in which social and economic divisions can be easily resolved as inclusivity and multiculturalism become the norm. Yet this network ideology does not dismantle Britain’s race and class divisions, but reinforces them, by intensifying the power of corporate capital.

In spite of all the pages that have been written about the internet, there is nothing to challenge what has become a new fully-fledged capitalist ideology; as a result that ideology has almost become accepted as ‘common sense’. The real internet debate has yet to start.

REFERENCES

Barkham, P. (2000, September 13). Gates rounds on protesters. Guardian. 5.

_____From Schengen to La Linea: Breaking down borders. (1999, August/September). Campaign Against Racism & Fascism. 4–6.

_____The asylum system: who profits? (2000, August/September). Campaign Against Racism & Fascism. 7.

Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cohen, N. (1999). Cruel Britannia: reports on the sinister and preposterous. London: Verso.

Deloitte Consulting. (2000). At the dawn of e-government: the citizen as customer. New York: Author

Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, philosophy, culture: interviews and other writings of Michel Foucault, 1977–1984. London: Routledge.

Freedland, J. (1998). Bring home the revolution: the case for a British republic. London: Fourth Estate.

Freedland, J. (2000, January 8). Us. Guardian Weekend. 8–16.

Harris, J. (2001). IT and the global ruling class. Race & Class 42 (4). 35–56.

Kundnani, A. (1998). Where do you want to go today? The rise of information capital. Race & Class 40 (2/3). 49–71.

Kundnani, A. (2000). ‘Stumbling on’: race, class and England. Race & Class 41 (4). 1–18.

Leadbeater, C. (2000). Living on thin air: the new economy. London: Penguin.

Mandelson, P. (1999, September 13). The new conservative enemy. Independent. 8.

Monbiot, G. (2000). Captive state: the corporate takeover of Britain. London: Macmillan.

Mulgan, G. (1998). Connexity: responsibility, freedom, business and power in the new century. London: Vintage.

Nairn, T. (2000). After Britain: new Labour and the return of Scotland. London: Granta.

Negroponte, N. (1995). Being digital. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sivanandan, A. (1989). New circuits of imperialism. Race & Class 30 (4). 1–19.

Thompson, B. (2001, January 22). The best an e-economy can get?. New Statesman Special Supplement. 4.

Performance and Innovation Unit. (1999). E-commerce@its.best.uk. London: Author.

Notes:

- Demos is a leading Blairite policy ‘think-tank’, which was established in the early 1990s by Geoff Mulgan and Martin Jacques. Its programme was to rethink the Left on the assumption that the historical aims of socialism are no longer tenable. ↩

- In 2000 the French government successfully legislated against the trade by French citizens in Nazi memorabilia on the internet, thereby defeating the conventional wisdom that cyberspace cannot be subject to individual national laws. ↩

- See, for example, Foucault (1988). ↩

- See the report in Barkham (2000). ↩

- Harris (2001) gives the following list of personal wealth in the IT sector: Jeffrey Bezos of Amazon, $8.9 billion; Lawrence Ellison of Oracle, $8.4 billion; Bill Gates of Microsoft, $71 billion. ↩

- See Sivanandan (1989). ↩